By Peter Bofin for the Cabo Ligado Monthly: January 22, published 18 February 2022

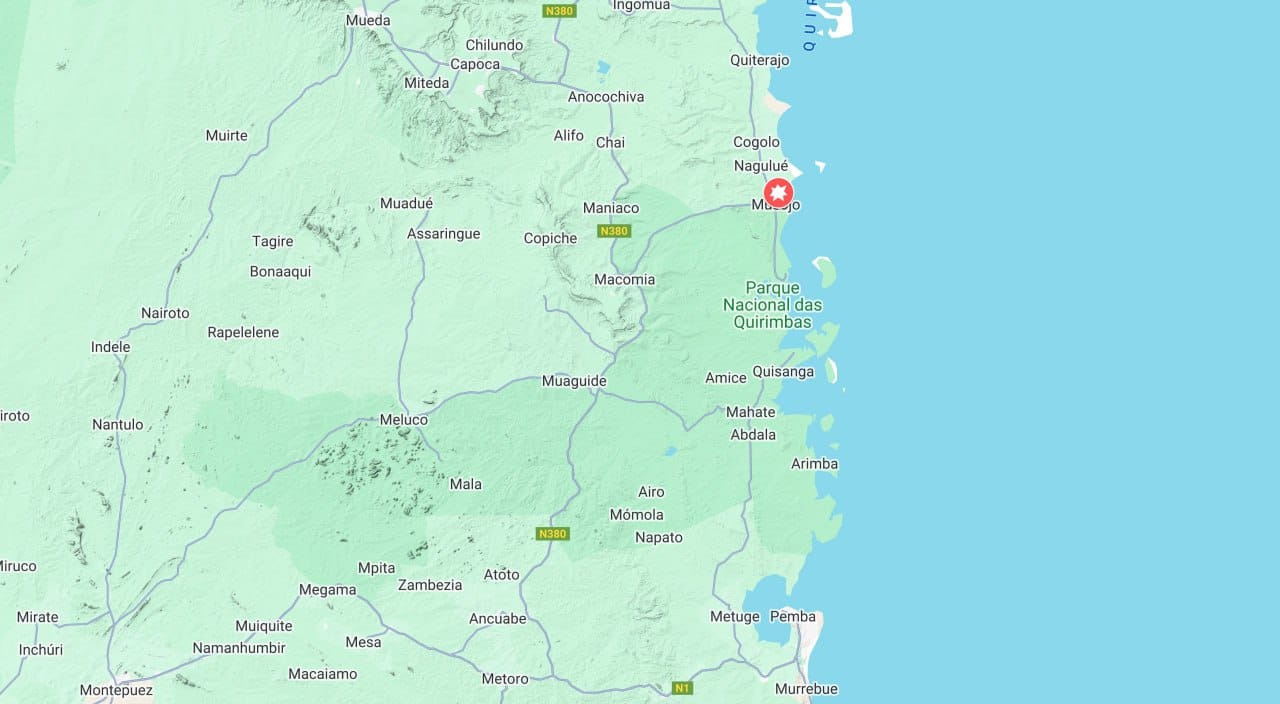

Tanzania has had a difficult month diplomatically. On 26 January, Vice Admiral Hervé Bléjean, Director General of European Union (EU) Military Staff appeared before the European Parliament’s Sub-Committee on Security and Defence to be questioned on progress with the EU Training Mission to Mozambique. He expressed his worry about “the Tanzanian attitude,” and said that Tanzanian officials were too focused “on how they should protect themselves from the situation” in northern Mozambique, rather than being part of the solution. Five days later, a Kigali news outlet published a piece comparing SAMIM unfavourably to the Rwanda Defence Force. It specifically accused Tanzania of being unable to control movement across the border, and that the Tanzania People’s Defence Force (TPDF) detachment in Nangade was unpopular with the “Muslim community” in Nangade. Subsequently removed from the news outlet’s site, the text remains online. On 28 January, President Samia Suluhu Hassan met with President Filipe Nyusi in Pemba. Speaking to the press, Nyusi spoke of “terrorists” crossing the common border, and the need for a dedicated approach. President Samia spoke blandly of having discussed “developmental and peace and security affairs.”

Tanzania is the only other SADC member, alongside Mozambique, directly affected by insurgent actions, so a focus on its posture towards the conflict is to be expected. It has long been known that networks in Tanzania provide vital logistical support to the insurgency, and that Tanzania has been an important source of recruits. Testing the claims, however, that Tanzania is indeed guilty of indifference is more difficult.

ACLED data confirm that movement across the border for insurgents remains an issue despite the deployment of SAMIM troops in northern Mozambique, and a long-standing state security presence on the Tanzanian side. Since August 2021, ACLED has recorded five violent clashes in Tanzanian border villages involving small armed groups crossing from Mozambique. Two wards have been hit twice in that period. Such raids are usually for provisions, and likely guided by Tanzanian members of the insurgency with detailed local knowledge of cross-border routes, and border communities. In at least one case, a raiding party was led by an insurgent originally from that village. Movement into Mozambique from Tanzania also continues, illustrated by arrests in December.

Those civilians that manage to cross the river into Tanzania fleeing clashes are still refouled across Unity Bridge to Negomano, and the very basic facilities provided there by the Mozambican military. Despite criticisms, this continues, most recently on 8 January when approximately 400 people crossed the river, fleeing an attack at Alberto Chipande village in Mueda district.

Whether these represent all clashes and crossings in that period, or just those that have come to light is difficult to assess. Certainly, there has been an effective media blackout in Tanzania on security issues along the border since 2017, if not before. Discussion of the conflict in Tanzania’s media is minimal, while civil society, and political activists also avoid the issue.

Access to the border remains restricted for the diplomatic community, though it has slowly improved since March last year. Diplomatic access to government decision-makers in Dar es Salaam too is restricted, with operations directed by the security forces at the highest level rather than traditional interlocutors. But this is not evidence of lack of engagement. Security channels are prominent in international engagement on the issue, whether through bilateral engagements with Mozambique and Rwanda, or through support to TPDF’s presence in Mozambique. The channels through which the Tanzanian government engages domestically and internationally are typically closed to other powers.

Consequently, the state dominates discourse on the conflict, and thereby great store is put on public pronouncements aimed at international audiences. Of these, there are few, and they are usually guarded, such as President Samia’s remarks in Pemba in January. But when a domestic audience is targeted, it is not unusual to see specific issues of recruitment for armed groups happening in border communities raised by the security forces. Examples can be found in footage of the police chief addressing villagers near the border, the Chief of Defence Forces addressing the press, or an officer addressing newly qualified cadets. It may therefore be understandable that international audiences see indifference, while selected national audiences may see concern.

Even if it is not evidence of indifference, this approach may support Vice Admiral Bléjean’s contention that Tanzania’s priority is its own security. Yet, as insurgent documents seized by SAMIM demonstrate, Tanzanian security is under threat. Stated insurgent objectives include free passage over the border; control of the banks of Ruvuma river; and the creation of permanent settlements in Tanzanian territory. While attacks have continued in Tanzania, they have mostly been for provisions, and not wholly offensive such as the October 2020 attack on Kitaya. Movement across the border continues at some level, but the lack of sustained offensives suggests it is not out of control.

The extent to which the insurgency controls the banks of the Ruvuma river remains unclear. Maputo’s Savana newspaper reports that small armed groups have been able to move with relative ease through Nangade district, through areas allocated to the TPDF and the Lesotho Defence Force. Savana reports residents’ complaints that SAMIM troops spend their time in their bases, arrive after attacks, and return quickly.

As one of the largest contributors to SAMIM, Tanzania can expect increased scrutiny if mooted external funding for operations emerges. This will come from funders, but also from governments, press, and civil society in fellow SADC countries, if not within Tanzania. As we have seen in January, such criticism can be more direct than the country may be comfortable with, and may require public communications that strategically engage with the wide range of interests with eyes on security in northern Mozambique, and southern Tanzania.