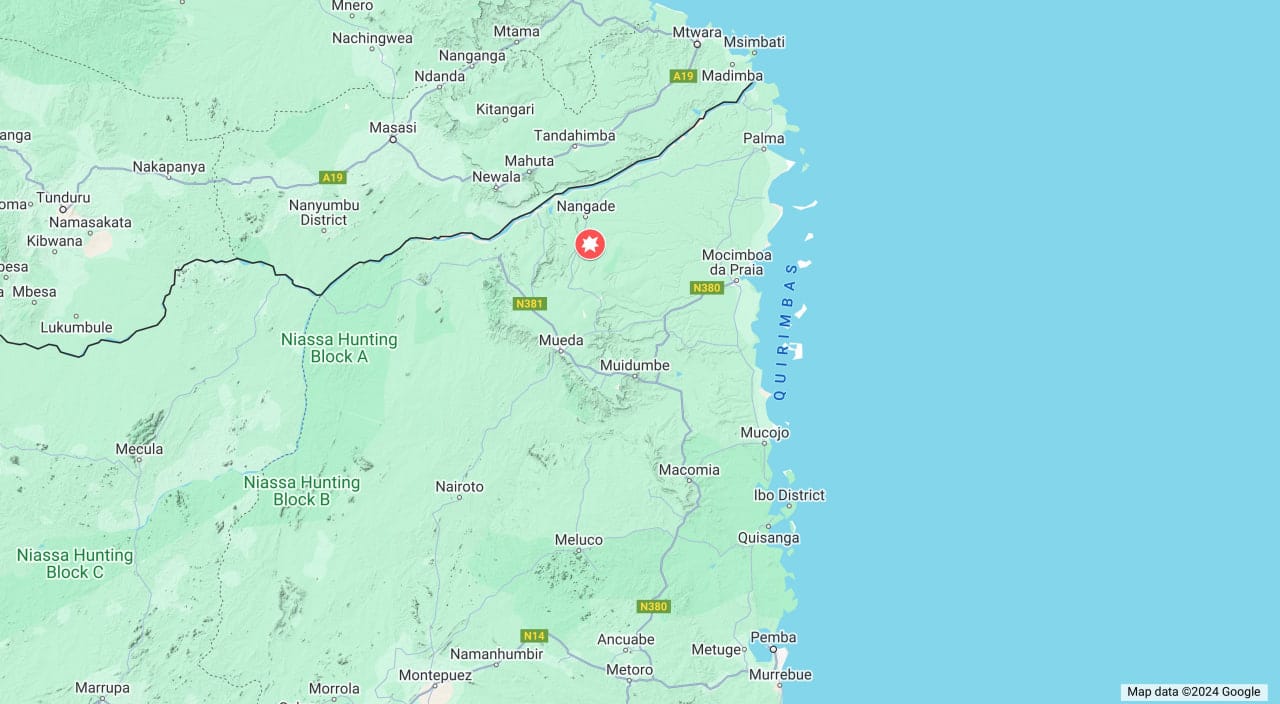

From the Cabo Ligado Monthly report for March 2023, first published on 17 April 2023

Amnesty, followed by reintegration, is perhaps the most consistent policy that Mozambique has taken on the conflict in northern Mozambique. General Commander Bernardino Rafael of the police made the first offer in December 2017, just two months after the conflict’s start. Repentance and surrender of weapons would be met with reintegration to “the country’s normal production and development processes,” he stated. President Nyusi made two amnesty offers in 2021. He followed this up in September 2022 in Mocímboa da Praia, presenting alleged insurgents at a public meeting in the town, who testified to the benefits of return. On 17 March, the district police commander urged people’s cooperation with the security forces so that insurgents could hand themselves in, and be rehabilitated. One week later, the district administrator again offered amnesty, and rehabilitation to those who hand themselves in, and asked the community to forgive them.

Offers of amnesty are not unusual in similar conflicts in the region. In Somalia, at least four offers of amnesty have been made to al-Shabaab members. Kenya offered its first amnesty in 2012, targeting those involved in al-Shabaab in Somalia, and another in 2015. Experience from that conflict suggests that communicating amnesty is the key issue. This is how individuals can be encouraged to exit from armed groups, and how communities can be prepared to receive them. Alongside this is the need to account for exit from armed groups, and return to communities that take place outside formal amnesty, rehabilitation, and reintegration programs.

Evidence from Somalia suggests that amnesty offers from the state can be significant drivers of exit from armed groups. Rehabilitation programs for former al-Shabaab fighters regarded as “low risk” are provided at the Serendi Rehabilitation Center in Mogadishu. “Low risk” indicates that they left al-Shabaab voluntarily, renounced its ideology, and are no longer a threat to the public. In research conducted there in 2015 by James Khalil et al. for the Royal United Services Institute, over two-thirds of respondents claimed that amnesty proclamations “substantially motivated their decision to exit.” It should be noted that the sample of 27 was small. However, their “low risk” category suggests that such proclamations are likely to have traction with a significant proportion of ‘foot-soldiers.’

Despite such a high proportion citing amnesty proclamations as being significant in their exit from al-Shabaab, Khalil’s report points out that without a clear policy and legal framework for amnesty, this can create expectations that are not met. Within this, determining who is eligible for amnesty and rehabilitation support is important. More recent work by Khalil in Nigeria argues that setting a high bar for eligibility for rehabilitation programs excludes a large cohort that could benefit from such programs. At the time of the research in March 2022, Nigeria’s Operation Safe Corridor program – a rehabilitation program in Gombe state in the northeast of the country – only received people who had been forced into Boko Haram, and not those who had joined for other reasons, such as ideological sympathy, or material reasons.

The opportunity to return to one’s community, how to do so, and any rehabilitation and reintegration support available, needs to be communicated effectively to those in armed groups. In practice, evidence from Serendi and Gombe indicated that people’s exit from armed groups was precipitated by a range of factors, including poor living conditions, fear of violence from either the group itself or government forces, and revulsion at the group’s actions. Exit itself can be realized if, firstly, there is awareness of amnesty and rehabilitation programs, and pathways to exit are clearly communicated. In Gombe, respondents mentioned both radio and leaflets – a method also used in Cabo Delgado – in this regard. Direct communication by family through mobile phone was also important to both “motivate and facilitate,” exit in Nigeria, as Khalil said. In Somalia, for respondents in the Serendi Center interviewed in 2017, radio and mobile phones were critical to the learning of amnesty, and in some cases facilitating exit through communication with family.

Studies such as those in Gombe and Serendi give critical insights into exit, but are necessarily limited in terms of the numbers of respondents, and their gender – both centers are male only. As the Gombe report points out, this reflects “the usual gender biases in this field.”

Having prioritized amnesty as a policy to induce exit, Mozambique is now faced with multiple challenges in meeting demand. These are related to screening, rehabilitation, and continuing efforts to prevent future recruitment.

Authorities will need screening mechanisms to assess the risks presented by insurgents who hand themselves in or are otherwise detained. That screening will help set the balance between rehabilitative and judicial responses. This will also need to be effectively communicated in order to set realistic expectations.

Perhaps the greatest challenge lies in responding to informal exit, which likely accounts for a considerable number in Cabo Delgado, and is perhaps inevitable when amnesty has been so clearly communicated. The UN estimates that the insurgent force has fallen from approximately 2,500 members to just over one-tenth of that. This strongly suggests that hundreds, if not more, of those involved in the insurgency in various roles have simply returned home, or made their way elsewhere. If large numbers have indeed returned voluntarily, and informally, the absence of clear screening, rehabilitation, and judicial processes may simply store up trouble.