From the Cabo Ligado Monthly report, published on https://www.caboligado.com/monthly-reports/cabo-ligado-monthly-march-2023

The pressures on the needs of those displaced by the conflict are felt in both centers for Internally Displaced People (IDP), and areas of origin, and this goes beyond the food assistance dimension. This has been the case as returns have been steadily increasing. According to the UN Refugee Agency, more than 350,000 people have returned to their areas of origin, but the number could be much higher. In the two weeks from 8 to 21 March, the IOM recorded around 3,978 arrivals, most of them (2,960) to the district of Mocímboa da Praia. Most of these, by far, are returnees.

There are broadly three factors driving the significant return in recent months. One is the continued poor conditions where displaced people are living, including constraints on food aid which has fallen short of what humanitarian organizations say they need, exacerbated by a surge in the number of IDPs in the second half of 2022. At the same time, the government, keen to portray a scenario of normality, has been encouraging people to return to their areas of origin by suggesting that basic services such as water, energy, education, and health have already been restored in some districts affected by violence. And finally, the reduction in violence has played a major role in persuading displaced people to move home. From February to March, political violence incidents involving insurgents dropped from 17 to 10, according to ACLED data.

The ongoing conflict has nevertheless had a devastating impact on thousands of displaced people in northern Mozambique, and profound damage to their mental health. As of November 2022, there were an estimated 1,028,743 displaced people, according to the IOM, which corresponds to 80% of Cabo Delgado’s 2017 population. Many of those have been forced to relocate not once, but several times. Trauma is significant for those who have lost loved ones and left their belongings behind. Children have grown up without access to education and basic services. Women and girls have suffered sexual and physical violence, both in conflict zones and in displacement camps. These mental and physical traumas are part of a prolonged crisis, and need to be properly addressed, particularly at a time when displaced people now face the challenges associated with starting over and reintegrating into their areas of origin.

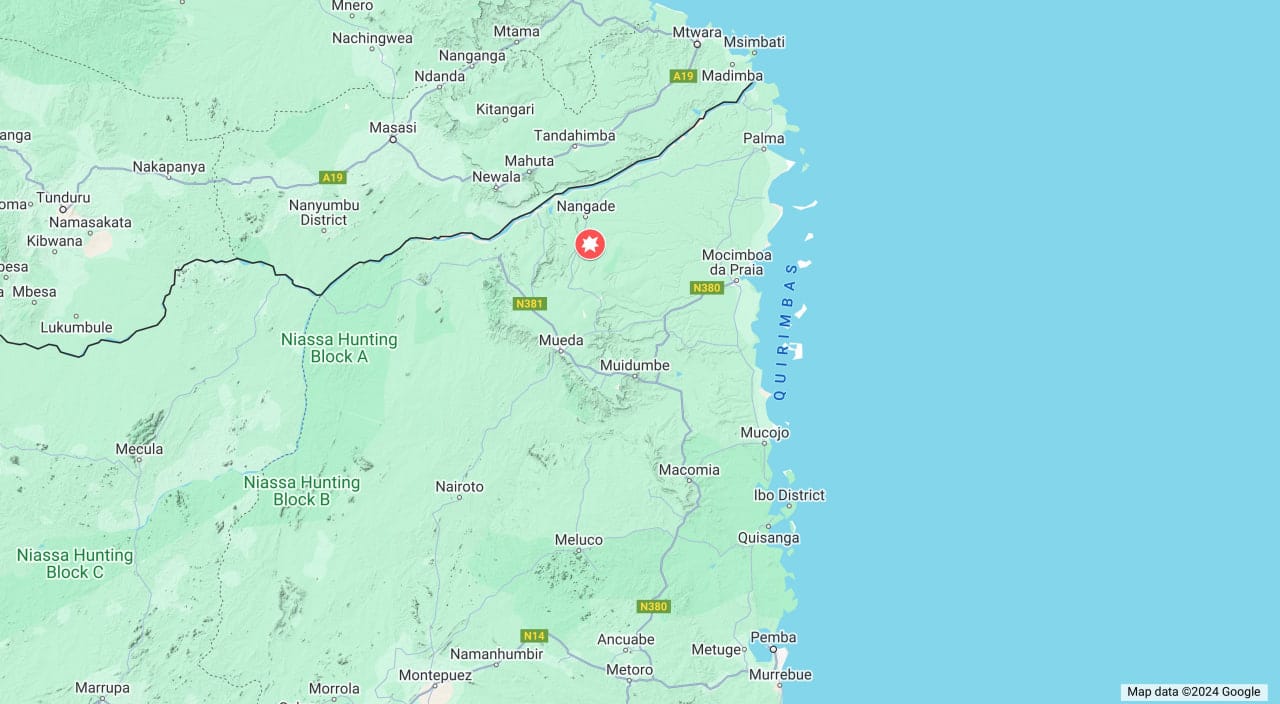

With most infrastructure partially or totally destroyed, health services are now severely limited in conflict-affected areas. According to ACAPS – an international non-governmental organization that provides humanitarian analysis – by December 2022, the districts of Macomia, Mocímboa da Praia, Muidumbe, and Quissanga had only one partially functioning facility per district, each serving an average of 109,000 people. Doctors Without Borders has resumed healthcare provision in the town of Mocímboa da Praia, using mobile clinics to provide consultations in the town and the most populous neighborhoods. But the services fall far short of serving the more than 87,000 people who have returned to Mocímboa da Praia so far, and most of the assistance provided is emergency care and does not directly address the psycho-social component. In other districts such as Nangade and Muidumbe, areas of limited access, the provision of psychosocial services is almost non-existent.

A number of technical and professional training initiatives for local youths are underway in Cabo Delgado. The Mozambican government and TotalEnergies are implementing a training program for young people from the districts of Palma, Mocímboa da Praia, Macomia, Quissanga, Muidumbe, Metuge, and Ancuabe in the areas of electricity, civil construction, metalworking, mechanics, among others, at the Alberto Cassimo Professional and Labor Training Institute in Pemba. On 30 March, 464 of them graduated, joining another 2,000 trained in the same area last year. This initiative aims to provide local youths with techniques and knowledge so that they can integrate into the local market.

The US Agency for International Development has teamed up with ActionAid Mozambique – a non-governmental organization – to implement a similar program, but targeting the southern districts. The program “Community Resilience and Youth Empowerment in Cabo Delgado,” which was launched in November 2022, aims to train 7,500 young people for the job market. While such complementary projects will contribute to lowering the likelihood of youth recruitment in areas of high vulnerability, they have a limited reach in the communities along the coast and in the north of Cabo Delgado, where most of the insurgents are believed to come from.

In the district of Ibo, which in February and March 2022 witnessed a series of insurgent attacks, the UN Children’s Fund is committed to resuming classes by building makeshift classrooms out of local materials and tents. This experience can be replicated in other areas of districts with high population returns to enable children to regain access to education.

A significant part of the psychosocial support, access to education, and health is concentrated in the southern districts of Cabo Delgado. So far, this has been justified by the insecurity in the northern districts of Cabo Delgado, which has limited the movement and operations of humanitarian organizations. However, the return of populations to their areas of origin needs a certain amount of stability. Security may be improving, but the lack of health, education, and livelihood services for the populations needs to be guaranteed. Without the involvement of international humanitarian organizations, the implementation of support projects may put the populations in difficult situations, given the inability of the Mozambican authorities to provide these services as a matter of priority. In Mocímboa da Praia, for example, the rehabilitation works underway include only the courthouse, supported by the UN Development Programme and the National Institute of Social Security. Infrastructures such as schools and hospitals are still untouched. Hence the absence of humanitarian organizations in districts such as Mocímboa da Praia, Palma, Muidumbe, Nangade, and Macomia may represent an important shortcoming, and put at risk the integrity and recovery of the populations.

There have also been some efforts by the government to reintegrate former insurgent fighters into their communities. Although controversial for not following any legal procedure, President Nyusi has made a series of amnesties to former insurgent fighters in the provinces of Nampula and Cabo Delgado throughout 2022. This is seen as an incentive for other fighters to lay down their weapons and join civilian life. However, no real rehabilitation and resocialization programs have appeared. This could lead to potential risks, such as reprisals in the communities, or even a threat to public order, as many of them have committed heinous crimes.