Cabo Ligado Monthly: November 2021

Throughout the conflict in Cabo Delgado, various reports from media organizations, research institutions, and humanitarian organizations have raised evidence of a number of people who have been detained by Mozambican security forces on suspicion of collaborating with insurgents in Cabo Delgado. A report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) published in December 2018 accused Mozambique's security forces of detaining, mistreating, and summarily executing individuals suspected of belonging to the insurgency. Amnesty International, in a report published in October 2020, accused the Mozambican army of carrying out executions and detaining journalists, researchers, and community leaders on suspicion that they were collaborating with insurgents.

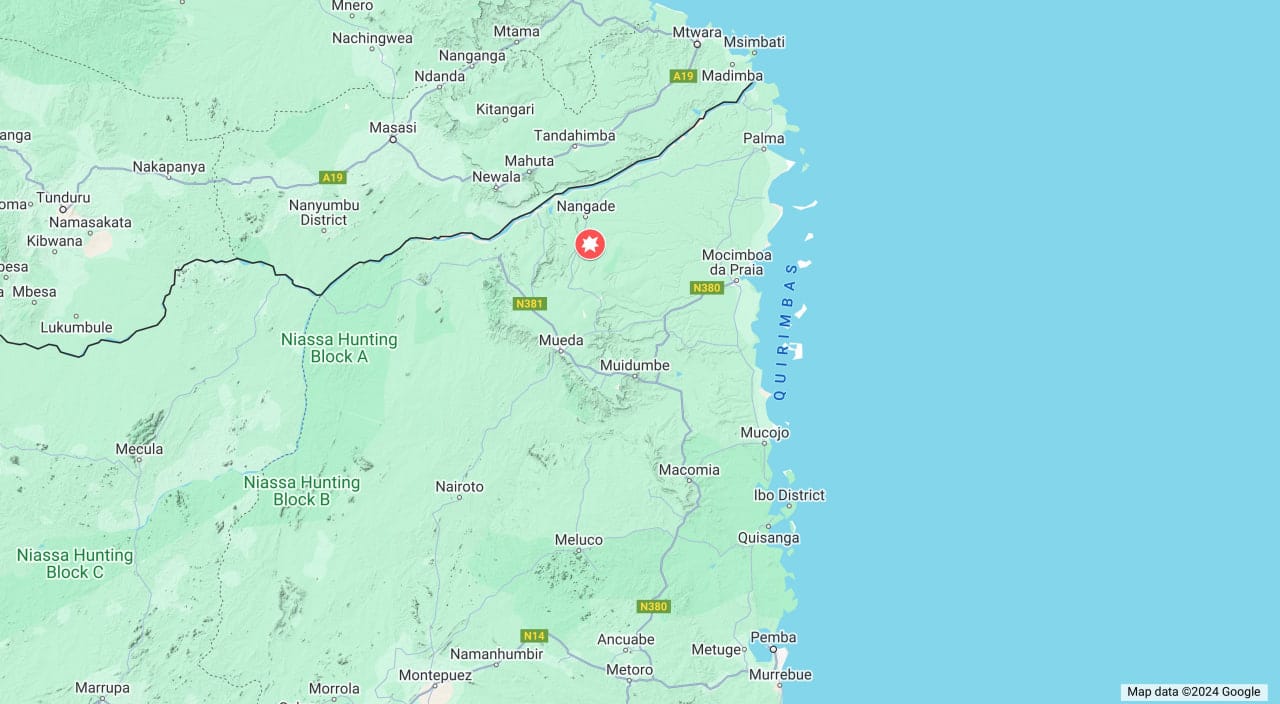

Incidents illustrating the situations described by human rights organizations continue to take place in the conflict-affected areas of Cabo Delgado. In November, local militia were reported to have killed two suspected insurgents in Macomia. Outside Cabo Delgado, in early November the southern province of Inhambane, police detained and later released 15 individuals from Cabo Delgado who were working for a Chinese fishing company off the coast of Inhambane after suspecting them of being members of the Cabo Delgado insurgency. On 19 October, local forces detained three civilians who were later handed over to the Mozambican police, accused of spying for the insurgents in Nangade. On 7 April, pro-government militias executed four individuals suspected of being members of the insurgency. Earlier in the year, police shot dead a suspected insurgent informant in the resettlement village of the Afungi LNG project in Cabo Delgado.

In the resettlement zones, sources report that displaced people fleeing the conflict are also suspected of collaborating with the insurgents, and in some cases accused of wanting to bring the war to southern Cabo Delgado. These accusations are based on the fact that the displaced persons speak Kimwani, a language often associated with the insurgency, and come from the areas of conflict in the province. Allegations of government prejudice against displaced people are reinforced by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, which reports that displaced persons face discrimination and random interrogations and harassment by Mozambican security agents.

The pervasive sense of suspicion directed at civilians in the conflict zone dates back to the start of the conflict in 2017. Displaced people from Mocímboa da Praia who are now in Nampula say there is a belief that the individuals who organized the first attack on Mocímboa da Praia on 5 October 2017 were of Mwani ethnicity. After order was restored in the area, several people from other ethnic groups suggested the police should search homes belonging to Mwani citizens, which created some dissatisfaction among them. From then on, sources say, the Mwani population felt marginalized and unprotected by the security forces, and refused to cooperate with the authorities in identifying possible insurgents. The behavior of elements of Mozambican security forces, characterized by mistreatment and summary executions of civilians, further reduced trust and collaboration between the military and the population.

Meanwhile, in Nangade district and other areas with smaller Mwani populations, collaboration with government security forces is stronger. In Nangade, for example, the population tends to report movements of suspected insurgents to local authorities, local militia, and defense and security forces. When the absence of a person is noted, the population seeks or consults the local leader to see if the person has requested a travel document to another place. If not, this is cause for investigation until the individual is located. In situations where the person is not located, it is assumed that he or she has joined the insurgency.

At the same time, throughout the conflict, government authorities have introduced mechanisms to ensure the identification of those suspected of belonging to and/or collaborating with the insurgency. One such mechanism is the issuing of a 'guia de marcha,' a document issued by the village chief to all those who want to move from one place to another. The document is issued at a cost of 100 meticais ($1.55). Whenever they are stopped by local forces, police, or soldiers, civilians must present this document. The document contains the name and contact details of their village leader, who can confirm whether the person has authorization to leave their village or not. If someone is stopped and is not carrying a guia de marcha, they can be subject to extensive interrogation.

Of course, some civilians actually are supporting the insurgency. Family members of insurgents and other civilian supporters have assisted insurgent logistical flows by providing supplies and withdrawing sums of money through mobile finance systems. According to a source in Macomia, the collaboration also occurs when family members request travel documents for relatives who are in the insurgency, which will allow them to flee or move elsewhere. A study conducted by Mozambique’s Rural Environment Observatory, a Mozambican non-governmental organization, on the social organization of the insurgents, noted that women who have joined the insurgents voluntarily or by coercion often carry out observation and espionage activities.

The Mozambican government denies the accusations of abuses made against it by human rights organizations, saying its actions are in defence of the country and the Mozambican people. Yet the evidence that groups like HRW and Amnesty International bring to bear is overwhelming, and there is little evidence that the state’s campaign of violence against those it views with suspicion is deterring such collaboration as there actually is between civilians and insurgents. As the conflict’s geographic footprint expands, it will only become more important to curb the government’s tendency toward violent repression of populations it deems at risk of collaborating with the insurgency.