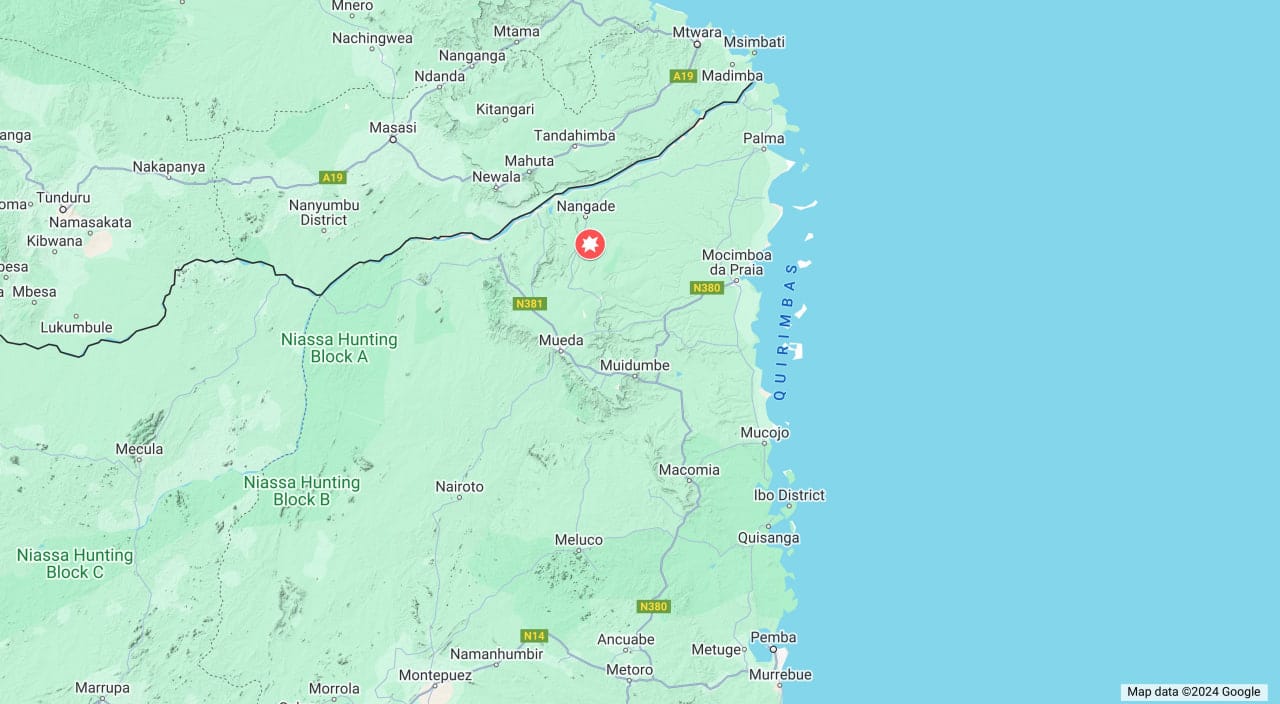

Testimonies from people who were in Palma, Cabo Delgado, when the town was attacked by insurgents on 24 March this year, dispel accusations of racism on the part of the Dyck Advisory Group, but point to a total failure of the government forces to protect the town and people in it — with one notable exception.

“There was no help from any authorities,” said one Mozambican entrepreneur who, like many business owners, was in Palma with the hope of generating business from the gas projects being developed nearby. He spent three days hiding at the Palma Residences hotel, before being evacuated by a DAG helicopter.

On the third day of fighting, he and others made a sign spelling “HELP” on the hotel lawn using bedsheets to attract attention from DAG’s helicopters which were circling above the town. It was not until the following day that one of them landed — but could only take two of the 17 people at the hotel.

“Everyone wanted to get in but we were too many,” he told Zitamar. “They took two women; obviously all of us thought maybe they won’t come back, but they did and they took everyone, two by two until everyone was at Afungi.”

“We were helped by that private company. I’m a black person, I was taken by them, I did not call them and I don’t know them. There was not one white person where we were. All of us were black race there,” Sakassaka said.

DAG, which was in its last week of a year-long contract to provide air support to police operations in Cabo Delgado, has denied accusations of racial discrimination in its partial evacuation of another hotel in Palma, the Amarula, where 220 civilians were sheltering.

DAG ran four rescue flights to the Amarula on 25 March, the second day of the attack on Palma, taking six people each time. In a statement responding to a report by Amnesty International, that accused government forces and DAG of “abandoning people during an armed assault simply because of the colour of their skin” , DAG emphasised that it “did not choose who would or would not be evacuated”, but simply “loaded the people that were sent to them for evacuation by the lodge manager … six people at a time”. This account is not disputed by any of the eyewitnesses who spoke to Zitamar News.

Around 220 civilians had sought refuge at the Amarula Hotel in Palma following the attack on the town on 24 March. According to Amnesty International about 200 were Black, and about 20 were white contractors. Amnesty said on 13 May said that “white contractors were prioritized to be airlifted to safety,” while Black people at the hotel “were left to fend for themselves”.

Zitamar has spoken to people who were at the Amarula, and people involved in coordinating the evacuation. A complex picture has emerged of evacuation plans which may initially have prioritised people in senior managerial positions at the various companies whose staff had sought shelter at the hotel — who were disproportionately white — but was later rectified. The plans were drawn up in preparation for a hoped-for evacuation by the Mozambican air force, which had recently taken possession of at least two large-capacity helicopters and whose pilots had received training in South Africa. At the first sign of trouble, however, those helicopters went back to base and did not take off again — leaving the skies to DAG.

DAG’s first evacuation flight prioritised taking the Black Mozambican administrator of the district of Palma, as well as women, children, and the sick or disabled, one white survivor who was not evacuated by helicopter told Zitamar. According to DAG, its four flights evacuated a total of six white people and 18 Black people of different nationalities.

The Amarula hotel manager, Timothy Robert, drew up lists of people to go in the evacuation flights, working together with two other hotel guests, including at least one Black Mozambican. He said no preference was given according to nationalities.

Robert himself was evacuated by a helicopter operated by Everett Aviation, chartered by his employer, Lynn Lury, the hotel manager. Along with Robert, five other hotel staff went in the helicopter: four Tanzanians and one Kenyan. Lury’s dogs were put in the hold, he told Zitamar, where flying regulations would not allow humans to be transported.

Everett Aviation confirmed to Zitamar that “every available seat was filled by a person (no more passengers could have been carried) and that only one passenger was Caucasian”.

Fleeing by road

The decision to evacuate the administrator first was also contested, according to a Black contractor at the Amarula who spoke to Zitamar on condition of anonymity. Some people argued that he should stay because he was a representative of the people, the source said.

"After the first three trips of the helicopter that carried the administrator, women and children there was an intention that the DAG should give priority to white people, but there was a resistance among us [blacks] inside," he said. "There even came a point where there was a split of two groups and each race was on its own side, but we decided it shouldn't be that way.”

Wesley Nel, a white South African who was at the hotel, told Zitamar that Robert — working with a Mozambican colleague of Nel’s — had lined up “expats and managers” to go next after the women and children, but “most of those managers said no, we are not leaving without our people.” He said the people at the hotel were divided into groups, with the largely white senior management, some of whom had satellite phones, trying to coordinate a rescue or escape attempt. “Whenever these guys got up and moved, everyone followed them — fearing that they would be left behind,” Nel said.

Some people argued that the white people should be rescued last, because if they went first, no-one would come back to save the black staff, Nel said — an account which tallies with one survivor quoted by Amnesty, who said: “We didn't want all white people to be rescued, because we knew that if all the whites left, we would be left there to die.”

At this point it was still believed that the Mozambican military’s larger helicopters, which could take 36 passengers at a time, were on their way. “So we said fine; three or four trips and we’re all out of there,” Nel said. But as time passed, it became clear that those helicopters were not on their way. The New York Times cited multiple eyewitnesses saying that the three helicopters only attempted to fly into Palma once, and quickly retreated under fire.

Those at the hotel then started planning their escape by road. They had hoped for air cover from DAG’s helicopter gunships — but the last time DAG’s helicopters arrived was to give cover for the Everett helicopter evacuating the hotel staff. Lionel Dyck, the founder of the company, alleged in the aftermath of the attacks that Total refused to supply his helicopters with fuel, preventing them from running more rescue missions.

The majority of those still at the Amarula then left in a convoy of vehicles that were at the hotel. Just two had bullet-proof armour, Nel said: a single-cab jeep owned by Vodacom, and a pick-up with an armoured canopy, into which the remaining women and children were put, he said.

The last vehicle to leave took the hotel security guard who had opened the gate for the convoy to leave. But insurgents were waiting up the road. “There were two ambushes,” Nel said. “The first was about 1.4km from the Amarula. The second one was about 5-6km after that.” Adrian Nel, Wesley’s brother, was shot and killed in the second ambush.

The largest group of survivors from the convoy made it to a beach at Quirinde, north of Palma, where they were picked up the following day by two boats operated by a company out of Palma. A source involved said all the expats were taken on the boats’ first trip, along with Mozambican migrant workers and some locals fleeing the area. The boats made another trip the following day to pick up remaining escapees from the Amarula. A DAG helicopter located and retrieved the body of Adrian Nel.

FDS inaction — save for one ‘amazing’ military position

A common theme from witnesses interviewed by Zitamar is the inaction of the government to protect locals and migrant workers in Palma. However, one expat praised the bravery of seven members of the military at a position close to the Afungi turn-off on the road heading south from Palma.

The source, who wanted to remain anonymous, was based at a camp near the military post when it was attacked — one of three simultaneous attacks that marked the beginning of the insurgent offensive in Palma.

“They came from two directions to attack the army camp at 3:30 in the afternoon,” he said. “We were all working happily along, and then people started running and shots started.”

Until then, he said, “Everyone was of the opinion that Palma was very well protected. We felt pretty safe.” The source had even told consultants visiting from South Africa two days earlier that he felt safer in Palma than South Africa.

“I was made to eat my words pretty quickly,” he told Zitamar.

It turned out that the military was “absolutely not” up to the task of defending Palma, he said, but the seven soldiers posted at the neighbouring military position stood their ground. When a military armoured car approached the post to resupply the soldiers, the source and eight colleagues saw an opportunity to escape.

“We took a chance and ran to it, and they took us to Afungi,” he said. “There were nine of us, four were expats and the rest locals. When they saw us coming one guy [a Mozambican soldier] went and stood in the open with an RPG [a rocket-propelled grenade], showing that he was protecting us and giving us the opportunity to get to safety.”

“I’ve got a lot of bad things to say about the Mozambican military but the guys at that bastion — just seven of them — if I see them again I’ll hug them. There were hundreds of insurgents, with new shiny weapons, and [the soldiers] just kept going. The Al Shabaab couldn’t take them. I don’t know what became of them in the end. But they were amazing.”

This article was produced by Zitamar and Mediafax under the Cabo Ligado project, in collaboration with ACLED. The contents of the article are the sole responsibility of Zitamar News.